The Jewish Roots of the Feast of Pentecost

by Rich Robinson | April 27 2021

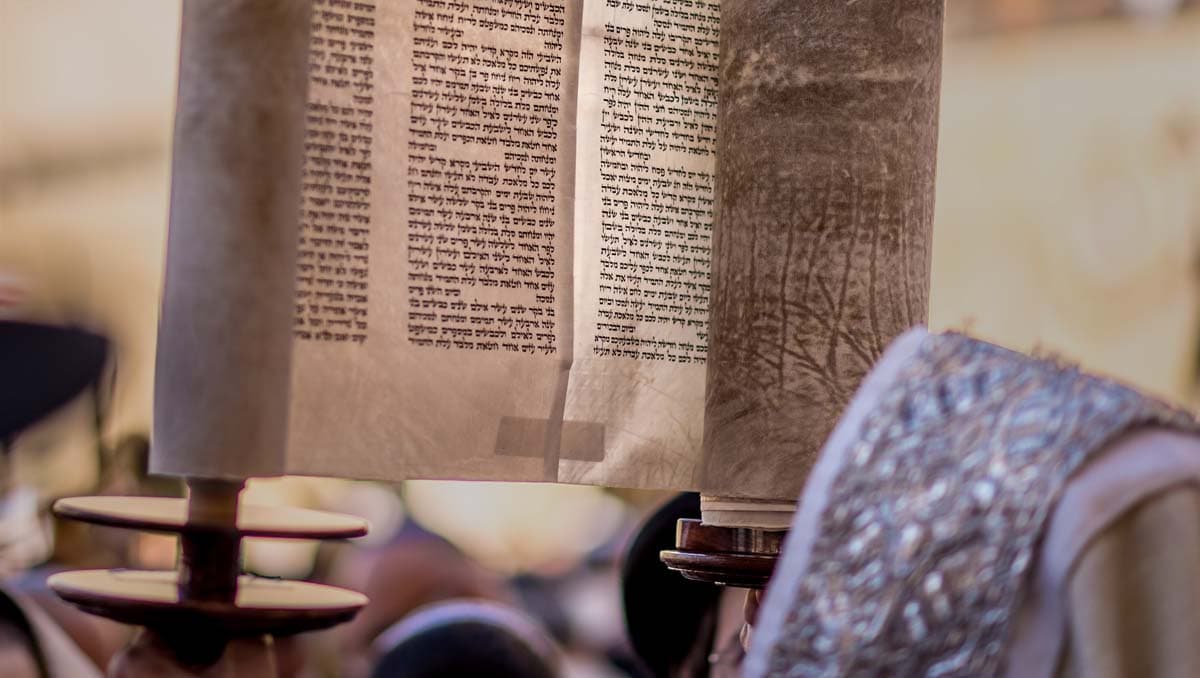

Pentecost is a Jewish Holiday

Pentecost is a prominent holiday on the Christian church calendar today. But did you know that it is a holiday from the Hebrew Scriptures that Jewish people still celebrate? In Hebrew, it is called Shavuot (rhymes with “a blue oat”), meaning “weeks”—and so it is known as the Feast of Weeks. Pentecost comes from the Greek word for “fifty” since it occurs fifty days after the preceding holiday, Passover.

Shavuot was originally a harvest festival, the second of two firstfruits occasions. In Leviticus 23, following the description of Passover, we read this:

And the LORD spoke to Moses, saying, “Speak to the people of Israel and say to them, when you come into the land that I give you and reap its harvest, you shall bring the sheaf of the firstfruits of your harvest to the priest, and he shall wave the sheaf before the LORD, so that you may be accepted. On the day after the Sabbath the priest shall wave it.” (vv. 9–11)

This was the first firstfruits offering, the harvest of barley, which included sacrifices. Next, we read about the second firstfruits occasion, the holiday of Shavuot:

You shall count seven full weeks from the day after the Sabbath, from the day that you brought the sheaf of the wave offering. You shall count fifty days to the day after the seventh Sabbath. Then you shall present a grain offering of new grain to the LORD. (Leviticus 23:15–16).

This time, it is the wheat harvest. Because it occurs seven weeks after the first offering (50 days, the day after the completion of the seven weeks), the holiday was known as Shavuot, or Weeks.

Once Israel was settled in the land and there was a permanent sanctuary, an entire ritual developed around the bringing of firstfruits. We were instructed to take some of the first of our harvest, place it in baskets, take it to the Tabernacle (later the Temple) and turn it over to the priest as an act of worship and gratitude to God for the land He gave us (Deuteronomy 26:1–11).

The Jewish people recounted the journey of faith of the entire nation.

This holiday was more than just the bringing of the first of the crops to present before God—it was a time to remember how Israel arrived in the land, which was something not to be taken for granted. Just as an individual might tell their story of their journey of faith, so our ancestors recounted the journey of faith of the entire nation. This meant never forgetting where they had come from in the past in order to continue to be thankful in the present. It meant remembering that the land was a gift from the Lord. And it was also an opportunity to rejoice, to enjoy the fruit of the land and, yes, even to party with family and visitors!

Pentecost/Shavuot: The Anniversary of the Giving of the Law

Though Shavuot continued to be oriented around agriculture and firstfruits, it was felt that this was the only holiday without a connection to Israel’s history. The ritual of Deuteronomy 26 made reference to that history, but most of that ritual was contained already in the holiday of Passover. And so over time, Shavuot took on a new character. The day God gave the Torah (Law of Moses) on Mount Sinai was calculated as falling exactly on the day of Shavuot. By the time of Jesus, in addition to being the firstfruit holiday, it had also become the anniversary of the giving of the Law.

It was on this very holiday, when tens of thousands of pilgrims were bringing their firstfruits, that the events of Acts 2 took place. According to the Mishnah (put in writing about AD 200), the processions to the holy city would be quite festive, and more than just wheat was brought as firstfruits, as we see from this description:

Those who lived near brought fresh figs and grapes, but those from a distance brought dried figs and raisins. An ox with horns bedecked with gold and with an olive-crown on its head led the way. The flute was played before them until they were nigh to Jerusalem; and when they arrived close to Jerusalem they sent messengers in advance, and ornamentally arrayed their bikkurim [firstfruits]. (Mishnah Bikkurim 3:3)

This time, though, it turned out to be a very unusual Shavuot!

The Day the Holy Spirit Came and Traditions Sprang to Life

Acts 2 tells the story of the giving of the Holy Spirit on Pentecost, after Jesus’ ascension. Note the bolded words:

When the day of Pentecost arrived, they were all together in one place. And suddenly there came from heaven a sound like a mighty rushing wind, and it filled the entire house where they were sitting. And divided tongues as of fire appeared to them and rested on each one of them. And they were all filled with the Holy Spirit and began to speak in other tongues as the Spirit gave them utterance. Now there were dwelling in Jerusalem Jews, devout men from every nation under heaven. And at this sound the multitude came together, and they were bewildered, because each one was hearing them speak in his own language. And they were amazed and astonished, saying, “Are not all these who are speaking Galileans?” (vv. 1–8)

There was both an unusual aural phenomenon (a great sound) as well as a visual one (tongues of flame) in the upper room on this day. This was definitely not a typical Shavuot occurrence! The disciples began to speak in languages they did not know and were understood by the other Jewish people in attendance no matter what their mother tongue was.

What was it all about? Going back to Exodus 19, when God first gave the Law at Mount Sinai (remember, by the first century, Shavuot was the anniversary of this event), we see significant parallels:

On the morning of the third day there were thunders and lightnings and a thick cloud on the mountain and a very loud trumpet blast, so that all the people in the camp trembled. Then Moses brought the people out of the camp to meet God, and they took their stand at the foot of the mountain. Now Mount Sinai was wrapped in smoke because the LORD had descended on it in fire. The smoke of it went up like the smoke of a kiln, and the whole mountain trembled greatly. And as the sound of the trumpet grew louder and louder, Moses spoke, and God answered him in thunder. The LORD came down on Mount Sinai, to the top of the mountain. And the LORD called Moses to the top of the mountain, and Moses went up. (vv. 16—20)

The same imagery continues in Exodus 20:

Now when all the people saw the thunder and the flashes of lightning and the sound of the trumpet and the mountain smoking, the people were afraid and trembled, and they stood far off and said to Moses, “You speak to us, and we will listen; but do not let God speak to us, lest we die.” Moses said to the people, “Do not fear, for God has come to test you, that the fear of him may be before you, that you may not sin.” The people stood far off, while Moses drew near to the thick darkness where God was. (vv. 18—21)

Could the phenomena of Acts 2 be related to those of Exodus?

The loud sound and tongues of fire in Acts 2 would have brought Exodus 19–20 to mind for some in attendance—especially since this was the anniversary of the giving of the Law, and Mount Sinai would have been on the minds of many. Could the phenomena of Acts 2 be related to those of Exodus? Quite likely. Jewish tradition had elaborated on what took place in Exodus, and that tradition was an even closer parallel to Acts 2:

The Targums, paraphrases of the Hebrew Bible into the related language of Aramaic, had this to say: “When a word had issued from the mouth of the Holy One, blessed be His Name, in the form of sparks or thunderbolts or flames like torches of fire … then a flame on the right and a tongue of fire on the left would fly through the air and return and hover over the heads of the Israelites, and then return and incise itself into the tablets.1

These ideas were certainly at the forefront of the minds of those present during the events of Acts 2. When many began to speak in other languages and were understood by the bystanders who came from a large number of surrounding nations, many were amazed, others were genuinely perplexed, and all asked one another, “What does this mean?” (Acts 2:11–12). Some even made fun of them: “But others mocking said, ‘They are filled with new wine.’ But Peter standing with the eleven, lifted up his voice and addressed them” (Acts 2:13–14)—these people were telling of God and His actions. There was a tradition that when God spoke His words, they “divided” into seventy languages:

From the Mishnah: “On the stones of the altar on Mount Ebal (Deut. 27) were inscribed all the words of the Torah in seventy tongues—i.e., all the languages of mankind.” (Mishnah, Sotah 7:5)

God was re-creating the events of Mount Sinai in a new way.

Though the Mishnah and especially the Talmud are from later than the first century, many traditions recorded in them go back much earlier. There is no doubt that on the day of Shavuot/Pentecost in Acts 2, the people present there were meant to understand that God was re-creating the events of Mount Sinai in a new way, and that the words of the disciples were meant to convey God’s own revelation to the people gathered. The loud sound, the tongues of fire, and the declaration in the languages of all present were traditions sprung to life.

Peter’s explanation is that Acts 2 is a fulfillment of the prophet Joel, that in the last days God’s Spirit would be poured out, with one of the results being “prophecy,” or speaking forth God’s words. The events of Acts 2 are the result of God’s Spirit at work.

The Meaning of Pentecost for Today

Acts 2 reveals that there is a new revelation happening. Jerusalem has become the location of re-creating Mount Sinai and the words of the disciples are a new word from God. This is not a negation and replacement of the Torah (Law of Moses). It is rather a fulfillment of the hopes of the Torah and the Prophets, a fulfillment of the hopes of the Jewish people in the appearance of the Messiah, and this calls for a new word from on high.

Further, there is a proclamation of God’s word to the entire world. The proclamation goes out to both Jewish people and non-Jews, so that all the world will eventually get to hear the message. While not quoted in Acts,2 this calls to mind Isaiah 56:7, “My house shall be called a house of prayer for all peoples.”

One day humanity will find reconciliation and unity through faith in the Messiah.

What a beautiful picture of unity and reconciliation! In Genesis 11, at the Tower of Babel, God confused the languages of the world so that people could no longer understand one another. In Acts 2 that confusion, at least for the moment, was undone. The promise of the gospel is that one day humanity will find reconciliation and unity through faith in the Messiah Jesus. In Acts, we have a “down payment,” or promise, that that will eventually indeed happen.

Firstfruits and the Promise of the Future

Shavuot/Pentecost was the second occasion of the Jewish calendar on which to bring the first of the crops to God. Seven weeks earlier at the barley harvest, firstfruits were brought, and now wheat was coming in.

When the first of the crop came in, it was a visual promise that the rest of the crop would follow. And so the idea of first fruits became a metaphor for the first of anything that would follow in larger measure. The New Testament is full of such images:

The resurrection of believers. “But now Messiah has been raised from the dead, the firstfruits of those who have fallen asleep. For since death came through a man, the resurrection of the dead also has come through a Man. For as in Adam all die, so also in Messiah will all be made alive. But each in its own order: Messiah the firstfruits; then, at His coming, those who belong to Messiah” (1 Corinthians 15:20–23 TLV). Jesus’ resurrection is like the first of the crops. It’s a promise and guarantee that more resurrection will follow, namely of those who place their faith in him.

The fullness of the Holy Spirit. “Not only so, but we ourselves, who have the firstfruits of the Spirit, groan inwardly as we wait eagerly for our adoption as sons, the redemption of our bodies” (Romans 8:23). As believers, God’s Spirit dwells in us individually and corporately. But the fullness of what that means lies in the future, when we experience the fullness of the Spirit’s work in our lives.

The enlargement of God’s people. “Greet also the community that meets in their house. Greet Epaenetus whom I dearly love, who is the first fruit in Asia for Messiah” (Romans 16:5 TLV). And, “I urge you, brethren—you know the household of Stephanas, that it is the firstfruits of Achaia, and that they have devoted themselves to the ministry of the saints” (1 Corinthians 16:15). In keeping with the meaning of firstfruits, Paul envisioned more coming to faith, both Jews and Gentiles.

The completion of redemption. “He chose to give us birth through the word of truth, that we might be a kind of firstfruits of all he created” (James 1:18). James writes that believers are the first evidence that God will redeem the universe on a grand scale. With all our imperfections and failings, God tells us that we are the first of something much greater. We are the firstfruits of redemption, God’s harbinger of the future.

* Bold emphasis added in all Scripture verses

Endnotes

1. Cited by Moshe Weinfeld, who writes: “Similar descriptions can be found in Targum Pseudo-Jonathan, in Targum fragments from the Genizah and in the Neofiti Targum.” See his essay “The Uniqueness of the Decalogue” in The Ten Commandments in History and Tradition, ed. Segal, Ben-Tsiyon and Gershon Levi (Jerusalem: Magnes Press, 1990), 40. Weinfeld also mentions Philo and Rabbi Akiva in reference to similar traditions.

2. Though elsewhere in the New Testament.

For Further Reading

For the Jewish traditions surrounding Pentecost, in addition to the sources in the footnotes, see Moshe Weinfeld, “Pentecost as Festival of the Giving of the Law,” Immanuel 8 (1978).