A Brief History of Messianic Jews

Everything you always wanted to know about Jewish believers in Jesus. Or some things, anyway…

by Rich Robinson | September 10 2025

In the Beginning…

It’s a well-known fact that the first followers of Jesus were Jewish. Non-Jews didn’t have the opportunity to believe in him right from the outset. Mostly, it was the word of Saul, also known as Paul, who brought the Jewish Messiah to the Gentiles—along with the (at first) controversial idea that they did not need to become Jewish in order to follow Jesus.

But the first of those who became disciples of Jesus were Jewish, and from all walks of first-century Jewish life. There were Pharisees who followed him, priests (most of whom were Sadducees), and amei ha-aretz, the common people who were not as well versed in Torah or the later traditions as were some others.

As Jews, they continued to live Jewishly. They attended synagogue services; they traveled to the Temple especially for the major holidays; they kept kosher (or some measure of it, depending on how observant they were). But then something happened!

The Gates Open…

Only a few years later, the opportunity to follow Jesus was extended to Gentiles. By the time of the late first century and early second century, non-Jews formed the majority of Jesus-followers. Afterwards, for a variety of reasons, many of these Gentiles came to conclude that the majority of Jews, having “missed the boat” about Jesus, were no longer the chosen people—a position known today as supersessionism or replacement theology. They further claimed that “the Jews” (often spoken of as a gigantic impersonal collective) misunderstood their own Scriptures (called the Old Testament by non-Jewish Christians) and interpreted them literally, rather than the “right way” (symbolically or allegorically).

The result was that Jewish followers of Jesus became increasingly marginalized. Those who insisted on keeping the Torah were looked on suspiciously. By the fourth century, Christianity had become the official religion of the Roman Empire. Several church councils met to consider a variety of issues, and among other things, decreed that the church should not recognize the Jewish calendar, nor should Christians live in any way like Jews. Thus began the institutionalizing of anti-Judaism, which in later centuries blossomed into antisemitism and acts of violence against Jews.

If there is an upside to this, it’s that the reason why the church declaimed so loudly against Jews and Judaism was that many Christians in the pews were all too happy to socialize with Jewish friends and neighbors, even participating in Jewish holidays. The church decrees (called canon law) legislated against those very things, often to no avail. Not until some centuries later did the average Christian come to dissociate from Jews and to participate in violent acts of antisemitism against them.

Yet even in the middle of the first millennium, Jewish believers in Jesus continued to worship as Jews and—as seen in some accounts in the Talmud—interact with other Jews.

The Picture Goes Dark

At some point, the trail of Jewish followers of Jesus disappears. The Middle Ages sees the rise of antisemitism, with Jews being widely accused of “killing Christ,” and with the advent of the blood libel (accusing Jews of killing Christian children in order to use their blood to make matzah for Passover). Violence and murder became all too common; for example, Christians heading to the Crusades in order to reclaim the “Holy Land” from Muslimswould routinely massacre entire Jewish communities en route as well as in the land of Israel itself.

We know of few Jews who became Christians during these centuries. Those who did were quite the opposite of the early Messianic Jews who lived Jewish lives in the midst of the Jewish community (as well as worshiping with other Jewish and Gentile believers in Jesus). Rather, these could be described not simply as Jews who chose to follow Jesus, but as converts to the Catholic Church. They sometimes spoke against the Talmud and against other Jews. Their reputation in the Jewish community was that of enemies of the Jewish people. What a change from how things were in the beginning!

A Renaissance after the Renaissance

Starting in the 1700s and even earlier, some Christians began to take an interest in the Jewish people as people, rather than as faceless enemies. In particular, their study of Scripture led many Christians to believe that God had a future for the Jewish people, and that this future lay in their return to the land of Israel.

At the same time, from about 1750 on, the Enlightenment (in the Jewish community, known as the Haskalah) brought both secularism as a replacement for religious faith (especially in Western Europe), and—as a concomitant—a certain lessening of the more extreme kinds of antisemitism. Some Christian groups believed that, rather than the Jews being disinherited by God and cursed by him, that they remained God’s people and that the message of Jesus should be brought to them.

By the mid-nineteenth century, bringing that message to Jewish people went viral, so to speak. Missionary work exploded among, mostly the Jews of Europe and North America, but also elsewhere, including in the land of Israel itself.

The Jewish community largely frowned on these efforts, yet there were a small but significant number of Jews embracing faith in Jesus, and—for the first time many centuries—doing so in the context of at least some Jewish culture. Special congregations and groups came into existence consisting largely of Jewish followers of Jesus worshiping in Yiddish and/or in the language of their own country. A notable example was Joseph Rabinowitz’s “Israelites of the New Covenant,” in Kishinev (today Chișinău in Moldava). Rabinowitz even wrote up a creed in the style of Maimonides’ Thirteen Articles of Faith (“I believe with perfect faith…”).

A “Hebrew-Christian” identity developed in which “Christian” meant the religion—faith in Jesus as the Messiah—while “Hebrew” designated the nationality.1 These Hebrew-Christian communities lasted well into the 20th century, with many Jewish followers of Jesus attending denominational Christian churches or “Hebrew-Christian” congregations.

And Today…

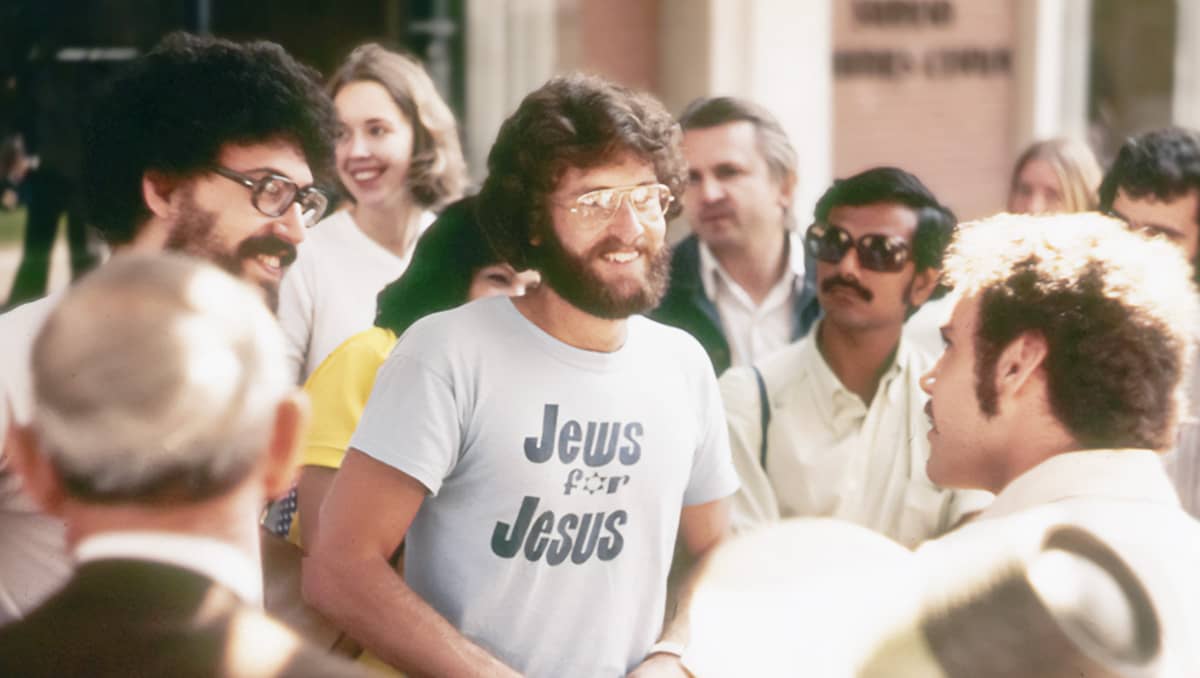

Starting in the 1970s, the idea of America as a “melting pot” (popularized by Jewish playwright Israel Zangwill in 1908) gave way to the emphasis on the diversity of ethnicities in North America.

As other ethnic groups did for themselves, Jews became more visibly and self-consciously Jewish. This also affected the shape of the community of Jewish believers in Jesus. The term “Hebrew-Christians” gave way to “Messianic Jews,” who often worshiped in “Messianic congregations” or “Messianic synagogues.” In those settings, much of the liturgy was adapted from synagogue worship and placed into the context of faith in Jesus. At the same time, many Jewish followers of Jesus worshiped in traditional churches, but with their Jewish identities fleshed out outside the walls of their church.

These Messianic synagogues also attracted non-Jews to their worship (coming full circle with the first-century, in which non-Jews known as God-fearers often attended synagogue worship).

Today, one can find umbrella organizations that seek to bring together Jesus’ Jewish followers. Among these, the Messianic Jewish Alliance of America (and of other countries) and the Union of Messianic Jewish Congregations are the most prominent.

Today, many Jews who follow Jesus proudly affirm their Jewish identity and lifestyle (though Jewish lifestyles vary widely among Messianic Jews), their support for the State of Israel, and their desire to see their fellow Jews embrace faith in Jesus as the Jewish Messiah.

Endnotes

1. This reflected how many conceived of Jewishness at the time—seen, for example, in the names of institutions such as the Hebrew Homes for the Aged or brands like Hebrew National Hot Dogs.