Chickens, Marshmallows, and Afflictions: A Yom Kippur Journey

Yom Kippur was never the same ... in a good way.

by Ruth Rosen | October 07 2024

Chickens

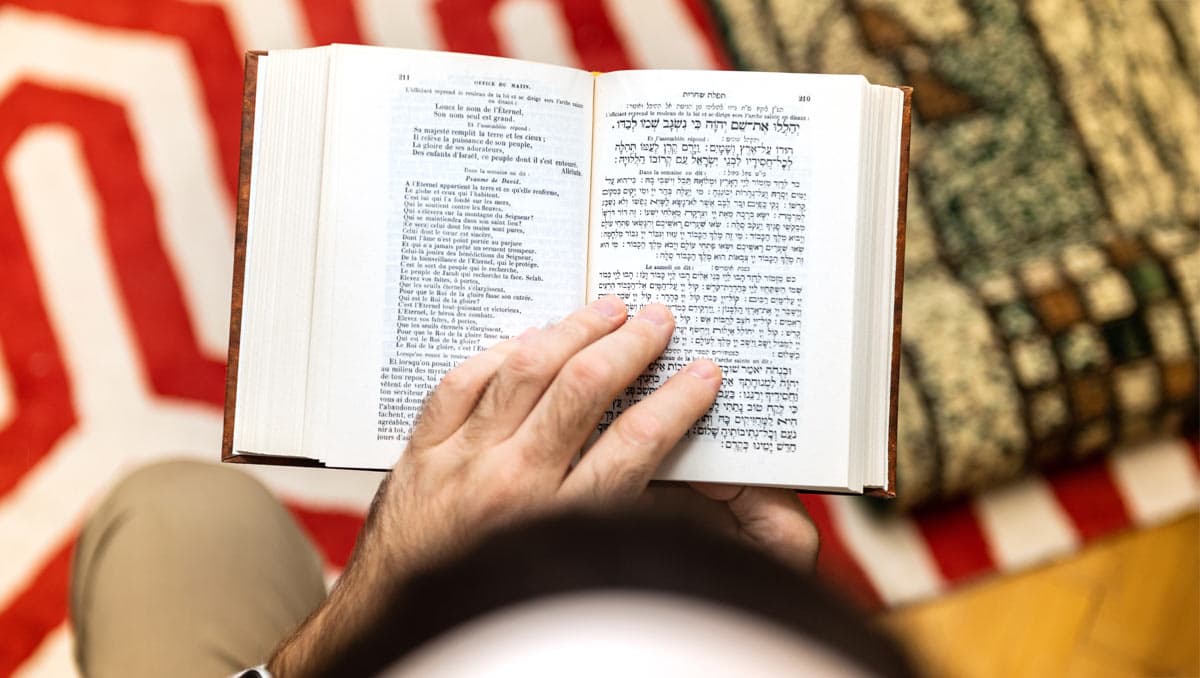

My dad, Moishe, was flipping through the machzor1 during the rabbi’s Yom Kippur message, searching for something to capture his 11-year-old imagination. He found a fascinating ritual that his family had never practiced under the section titled “For the Day of Atonement.”

According to the prayer book, the man (or woman) of the house was supposed to take a rooster or chicken and swing it over their head three times while saying, “This is my change, this is my redemption. This rooster (or chicken) is going to be killed, and I shall be admitted and allowed to live a long, happy and peaceful life.”

Moishe silently nudged his father and pointed to the instructions. His dad quietly responded, “We don’t do that anymore.” Moishe then showed the page to his little brother, Donny, who grinned at the thought of swinging a live chicken over his head.

When they got home, Moishe asked his dad to tell them more about the mysterious ritual. His father explained that after the ceremony, you couldn’t eat the chicken because it was a sacrifice; you had to give it to somebody in need. Donny loved the idea. “Can we do it, Dad? Can we do it?” Their father replied, “We’ve got better uses for chickens around here.”

Years later, the sun had gone down on another Yom Kippur, and 17-year-old Moishe was musing as he waited for the bus to take him home. He’d fasted along with the rest of his family, and they had dutifully attended services. Along with the rest of the congregation, they had confessed a litany of sins, including intentional and unintentional wrongs that had been done, as well as right things that had been left undone.

Later, when most headed for home to share a long-awaited meal, my dad went to the sporting goods store where he was a salesman, and worked a few hours.

His Jewish education had ended after his bar mitzvah, and like so many before (and after) him, my dad began to question what he did or did not believe about God. But he never questioned his Jewish identity. And in those days, fasting and attending synagogue on Yom Kippur were facts of Jewish life. But there was a lingering question: Had anything spiritual actually occurred?

As he waited for the bus home, a man who looked just a few years older than my father struck up a conversation with him. The stranger, whose name was Orville, was not Jewish but very inquisitive. Before long, my dad found himself explaining about Yom Kippur, particularly about fasting and prayer.

“So what does it all mean?” Orville asked.

Dad shrugged. “It means that my sins are supposed to be forgiven.”

“Do you feel your sins are forgiven?”

“Who knows?” Dad shrugged again, and with the bus approaching, he figured the conversation was over. But Orville took a seat near him and said, “I believe there is a way to know that your sins are forgiven.”

Dad could tell he was winding up for the pitch. Sure enough, Orville went on to say, “I believe that Jesus died for my sins and made it possible for me to know God and find eternal life.”

My father was not surprised that Orville was a Christian. But he was very surprised that Orville knew a lot about Yom Kippur—and as he explained his Christian viewpoint, it sounded as though the whole thing was a Jewish idea.

“The part about Jesus dying to take the punishment for people’s sins,” Orville said, “was pictured in the original observances of Yom Kippur in Bible times. The Jewish high priest placed his hands on the scapegoat and recited the sins of the people, and the goat was then led out into the wilderness, far from the camp of the Israelites. Another goat was sacrificed, and its blood was sprinkled on the altar as an atonement [covering] for sin.”

It all sounded strange, but my father couldn’t dismiss it as Christian nonsense

It all sounded strange, but my father couldn’t dismiss it as Christian nonsense because clearly, Orville was describing things from the Torah. And to his utter dismay, my father found that it made sense to him. He recalled what he’d seen in the prayer book years before. If Jewish people could recite something about a chicken’s death somehow bringing life and peace to a human being, why was the story of Jesus dying for people’s sins considered so very un-Jewish?

Before they parted, Orville challenged him to find out what Jesus actually said and did, and he gave him a New Testament.

My dad accepted it out of politeness, but later he thought, If I read it, I might be dumb enough to believe it. And, because he’d always been taught that Jewish people do not believe in Jesus, he tossed the book in the trash.2

A few years later, the things Orville had said resurfaced. My mother, Ceil, had been raised more Orthodox, but she had become curious about Jesus and began reading the New Testament in secret. Before long, she was convinced that Jesus was the promised Jewish Messiah and the key to peace with God.

Mom told Dad about her new faith and began showing him prophecies of the coming Messiah from the Jewish Bible. That is, she did until he emphatically told her to stop. But then, he couldn’t stop thinking about it himself. Eventually, he had to admit that he actually did believe.

From that moment, the enormity of Jesus’ sacrifice filled my father’s heart and mind. Throughout the rest of his life, Dad was eager to share the life and hope he’d found in Jesus with others.

So, I was raised with a strong Jewish identity . . . and also was taught that believing in Jesus was a very Jewish thing to do. Like all kids, I had to decide for myself what I believed. And it’s been a process.

Marshmallows

I first connected with Jesus personally as a six-year-old. That’s how old I was when I realized there was something ugly inside me. No one had pointed it out, because no one knew my secret thoughts. I didn’t have a name for it, but the ugliness inside me was envy, and it caused me to think and do ugly, selfish things.

Once, at the grocery store, my mom said “no” to my request for marshmallows. As soon as no one was looking, I began literally pinching the bags of marshmallows. I was trying to smash at least one marshmallow in each bag to ruin them! I imagined with satisfaction another mom picking up bag after bag of marshmallows and telling her daughter, “I’m sorry, honey. These marshmallows are smashed. Maybe another time.”

I felt that God would be right to reject me.

It may sound silly, but I knew I’d done something rotten, and my satisfaction soon turned to embarrassment and shame. But that didn’t stop me from similarly acting out my envy over other things—albeit most of my “acting” was on the stage of my imagination. Outwardly, I was shy and sweet, but inside was a meanness that I knew was wrong. And I knew that God saw it. I felt that he would be right to reject me, but I wanted him to forgive and accept me. One day, my mom sensed I was troubled about something, and I told her about the ugliness inside. She assured me that I could ask God to forgive me based on what Jesus did, and I took my first step of faith in him.

Years went by, and I continued to believe in Jesus, but I became more lenient with myself. I didn’t behave badly outwardly, but I habitually filled my imagination with self-righteous scenarios. I was the star of all my daydreams, winning every imaginary argument, always able to perfectly articulate what (I thought) anyone I was at odds with needed to hear.

I didn’t realize at the time that I was being self-righteous. But there were times when I knew I was imagining things I shouldn’t — grown-up versions of squashing marshmallows. I was embarrassed and ashamed and apologized to God often, but my apologies never led to change.

When Yom Kippur came around, some years I’d fast, but mostly to have a shared experience with other Jewish people. I knew that the tradition of fasting came from the biblical command to “afflict yourself” on the Day of Atonement. But God had been forgiving my sin since I was six, so why should I bother afflicting myself?

I often attended messianic Yom Kippur services, again for a shared Jewish experience. As we prayed through much of the traditional liturgy, I found the long recitation of sins in the prayer known as the Al Chet somewhat irksome. As far as I could see, I had committed very few of those sins. Why did I have to confess other people’s sins?3

And yet, I would get a bit of clarity when we confessed to God what we had NOT done, which included the two commandments that Jesus had identified as the greatest in all the Torah:

We have not loved You with all our heart, all our soul, all our mind, and all our strength.

We have not loved our neighbor as ourselves.

I told myself that nobody could live up to that high standard of love. But that did not take away my nagging discomfort over not loving God or my neighbor nearly well enough. I began to ponder it throughout the year, not just at Yom Kippur. The more I thought about it, the more I knew I ought to change. But I didn’t know how much or how to do it.

Afflictions

How does knowing that we need to change get energized into an overwhelming desire to change?

It turned out that, contrary to what I’d thought, what I needed was to be well and truly afflicted. I’ve never embraced affliction willingly—not even at Yom Kippur—but God, in his mercy, arranged it.

It happened when the gnawing anxiety I’d had about losing my parents since early childhood exploded into an acute fear. It was 2016, and my mother had been diagnosed with congestive heart failure. She was not in imminent danger, but my dad had already passed in 2010, and now the clock was ticking for my mom. I desperately needed to be wrapped in a love that would never die. The only love I knew of like that was God’s.

I could not find that kind of love in myself.

So, I began talking to God again about how I needed to love him more, but this time, it wasn’t from a sense of religious duty. It was a matter of self-preservation! I told God that I urgently needed to love him above everyone and everything else. But I felt helpless. I could not find that kind of love in myself.

And that’s when he helped me . . . by opening my eyes to a painful truth. I was horrified as I found myself admitting to God that while I loved all the good things he had given me, I honestly didn’t know if I actually loved him just for who and what he is—at all!

Of course, it’s OK to love God for all the great things he gives and does for us. That’s probably where our love for God (or anyone) starts. But something is horribly wrong if love never gets deeper than that.

We probably all know people who only love us for what we can do for them. They’re self-centered users. I always thought I was better than that. But suddenly, I knew that I wasn’t.

I had been using God all along. And God knew it. But he was still reaching out to me. My heart was utterly shredded. That pain, that affliction, led me to a repentance that I will never regret. And from the moment I truly repented, God began forging a bond with me that I will treasure forever.

God, in his mercy, had pulled off my spiritual blinders. It’s as though he was telling me,

This is what I’m forgiving you for. Not just some laundry list of bad behavior. I’m forgiving you for not loving me—all the rest is a byproduct of that. I know that you sometimes doubt my love for you, and that makes it hard for you to love me. But that’s why Jesus suffered and died. Whenever you doubt my love, remember that everything Jesus did was because I love you.

A New Holy Day

How we can love an unseen God will always be somewhat of a mystery, but he gave us something concrete to help us grasp it—the enormous and altogether personal love that Jesus showed in his life, death, and resurrection. Yom Kippur traditions can help us see that Jesus, whom people could see, and touch, and hear, was God’s plan all along.

The New Testament claims that those sacrifices point to the greater reality.

The mysterious chicken ritual that so fascinated my father and his brother was an attempt to recapture the visceral experience of the Temple sacrifices, which were even more gut wrenching. Imagine holding a life in your hands and then ending it as a sacrifice. That graphic illustration showed how falling short of God’s goodness drains the spiritual life from us, just as the life was drained from the animal. We needed that painful truth in order to repent and receive God’s forgiveness. The New Testament claims that those sacrifices point to the greater reality of the one who came to stand in our place in a way that no animal ever could.

I used to resent reciting sins that I had not done. But Jesus actually suffered and died for sins that he had not done! I did not want to hold myself accountable to God’s standard of love that seemed way too difficult to meet. But Jesus met that standard perfectly, and at great cost.

In Jesus, we can have the ultimate Yom Kippur—the ultimate affliction and the ultimate restoration—living in our hearts every day and helping us to love God and our neighbors more and more.

God doesn’t really need our good intentions, our good deeds, or bags of unsquashed marshmallows. He just wants us. For me, Yom Kippur is a cherished reminder of that life-transforming truth.

Endnotes

1. High Holiday prayer book

2. These recollections are taken from my father’s biography, (authored by me) Called to Controversy: the unlikely story of Moishe Rosen and the founding of Jews for Jesus (Nashville: Thomas Nelson, 2012).

3. I later realized that every sin on that list stems from a failure to love God. So, the seeds of all those sins were there in my heart, even if they had never bloomed into behavior.