Siddur Vs. Scripture

by Jews for Jesus | July 01 1987

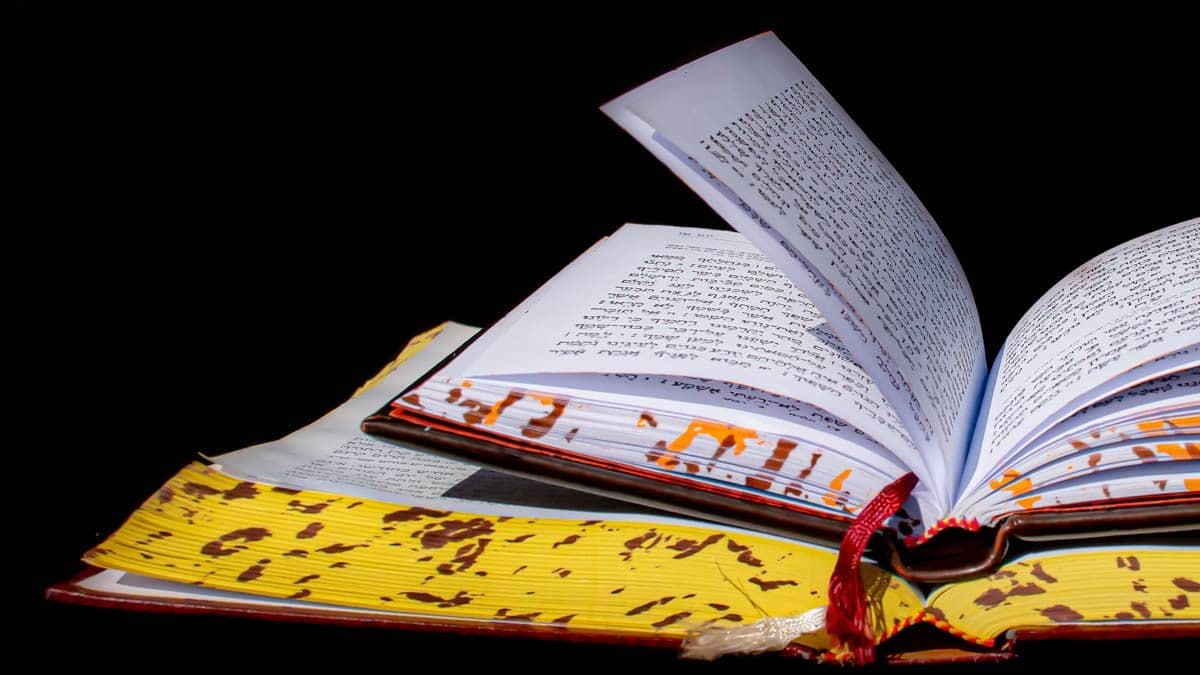

While Jewish people regard the Torah or Five Books of Moses as the most holy portion of religious literature, the book closest to the heart of a religious Jew is his siddur, the prayer book. Except for the weekly synagogue readings, the Holy Scriptures may be unfamiliar to him, but the prescribed prayers of the siddur are upon his lips every day. A Jewish child learns to recite Hebrew by rote, in order to pray from the siddur in its original language.

Because the siddur occupies a central place in the life of a practicing Jew, it provides a fascinating introduction to Judaism for interested non-Jews. Nothing within the pages of this book can be considered peripheral to Judaism. Here lies the expression of the Jewish heart, as my people through the centuries have wrestled with their religious feelings.

Those who are familiar with the Old Testament portion of Scripture will find that much of the siddur seems familiar to them. The prayer book abounds with psalms, as well as quotations from Scripture and poetry that contains biblical allusions. Unfortunately, however, it is not possible to show a Jewish person the gospel from the siddur.

There is a point where the siddur and Scripture part company, as it were. This comes about over the matter of sin and atonement. An early point to be made in proclaiming the gospel is that God waits us to be in a relationship with him, and that relationship is the basis of a worthwhile life. Here the siddur would agree, as every morning after a religious Jew puts on his prayer shawl, the siddur directs him to recite Psalm 36:7-10:

How precious is thy lovingkindness, O God! And the children of men under the shadow of thy wings they take shelter. They shall be satisfied with the fatness of thy house. And of the river of thy pleasure thou shalt make them drink. For with thee is the fountain of life; In thy light shall we see light. Continue thy lovingkindness to them that know thee, And thy righteousness to the upright in heart. (Philips Daily Prayer Book, p. 9)

What more beautiful description of the joys of knowing the Lord could we find? But the gospel confronts us with a problem: we are sinners and therefore separated from God. In responding to this problem, the siddur does not bear out the biblical point of view, i.e., that fallen humanity is incapable of pleasing God unless it is regenerated. During the morning prayers from the siddur there is a quotation from Berakhoth 60b in the Talmud:

My God, the soul which thou hast placed within me is pure. Thou hast created it; thou hast formed it; thou hast breathed it into me. Thou preservest it within me; thou wilt take it from me, and restore it to me in the hereafter.

In contrast to the scriptural teaching that as descendants of Adam we all have inherited God’s image in warped fashion, the Judaism of the siddur sees humanity as basically good and each soul as a new and pure creation of God. Yet even the siddur must deal with the inner quirk in humanity that we recognize as the sin nature. It calls this flaw the evil impulse,” which is able to be overcome by good works. One prayer from the siddur states:

Let not the evil impulse have power over us…make us cling to the good impulse and to good deeds, and bend our will to submit to thee.

The siddur treats sin as a less serious matter than the Bible does. The Judaism of the siddur and of the modern rabbis is not the religion of the Old Testament. It is instead a system adapted to an age in which there is no temple and there are no blood sacrifices for atonement. Theoretically, however, the need for the temple is acknowledged by Orthodox Jewish people in the following prayer:

May it be thy will, Lord, our God and of our fathers, to have mercy on us and pardon all our sins, iniquities and transgressions, and rebuild the temple speedily and in our days, that we may offer before thee the daily burnt offering to atone for us, as thou hast written in thy Torah through Moses thy servant.

At this point, the order of daily sacrifice from Numbers 28 is read, and then the following words are said:

Sovereign of the universe! thou didst command us to offer the daily sacrifice in its appointed time; and that the priests should officiate in their proper service, and the Levites at their desk, and the Israelites in their station. But, at present, on account of our sins, the temple is laid waste, and the daily sacrifice hath ceased; for we have neither an officiating priest, nor a Levite on the desk, nor an Israelite at his station. But thou hast said that the prayers of our lips shall be accepted as the offering of steers. Therefore, let it be acceptable before thee, O Lord, our God! and God of our ancestors, that the prayers of our lips may be accounted, accepted and esteemed before thee, as if we had offered the daily sacrifice in its appointed time, and had stood in our station. (Philips Daily Prayer Book, p. 42, 43)

Those two words, “as if” are the cornerstone of rabbinic Judaism. After Yeshua rose from the dead, God allowed the Temple to be destroyed. It was a sign of judgment upon Israel, to let us know that the Messiah had come, and atonement now was to be found in him, not in the animal sacrifices. At that point, many Jewish people believed the followers of Yeshua who proclaimed this message in their midst. But mainstream rabbinic Judaism parted company with them, declaring that prayers and good deeds were valid substitution for the sacrificial element of the Torah (Law).

They decreed that Judaism should continue as if what we were doing was observing the Law of Moses. Jewish people today cannot keep the Law of Moses. Most of it cannot be observed outside of the State of Israel, or without a functioning temple service. The rabbis salvaged the few remaining commandments and expanded the rules for keeping them. This contrived weightiness adds so much to the observance of Judaism that its adherents think they are keeping the entire Law when they are not.

The fact remains that the Temple and its sacrifices, which were central to the Law of Moses, are missing. It is not sufficient to go on as if the Temple were still standing. Judaism needs to return to the Scriptures and find out why the Temple is missing. It needs to discover that the Messiah came and died for sin, and that only through his sacrifice can the Torah be fulfilled.

The siddur, the Jewish prayer book, contains some beautiful prayers and lofty concepts about God, but it is incomplete. It cannot bring the Jewish people into a correct relationship with the Creator. The siddur misses the mark at the point where it veers away from the teachings of Scripture.